As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

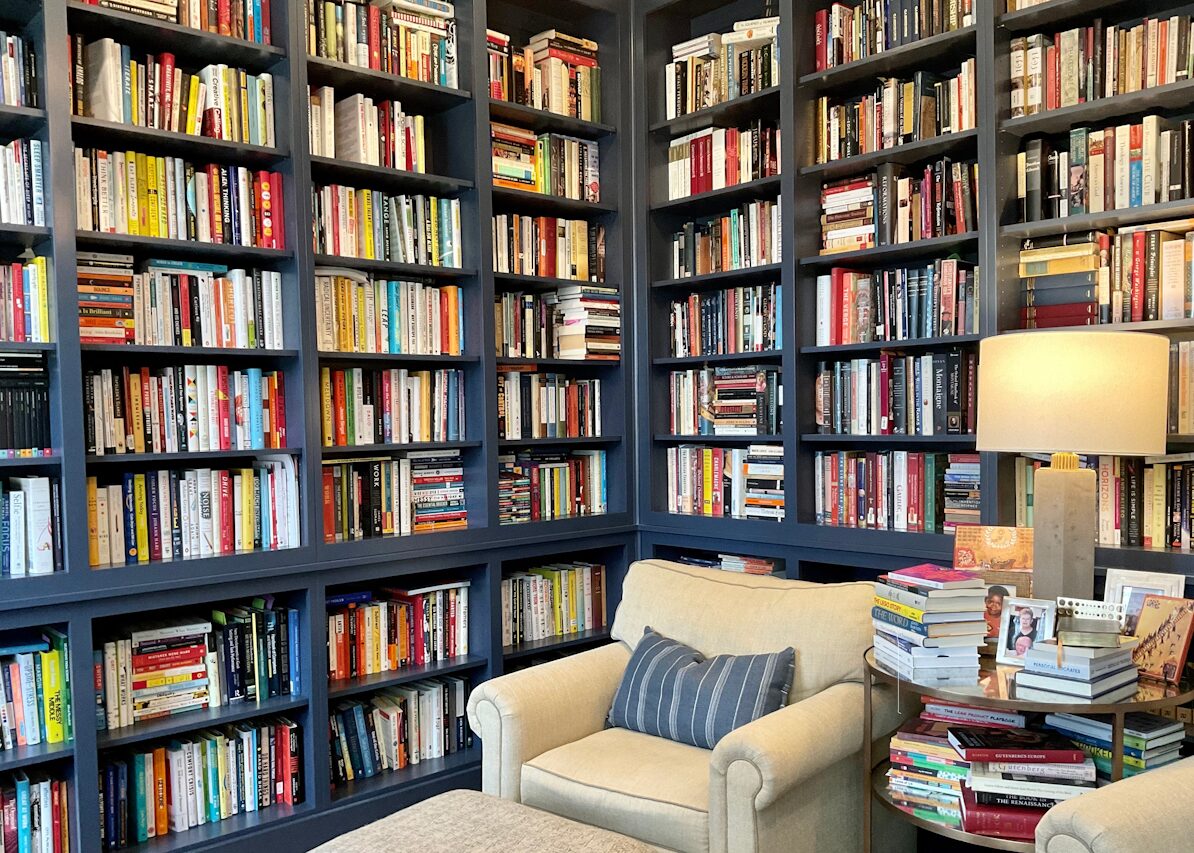

There’s something about walking into someone’s home and discovering a thoughtfully curated library that instantly earns respect. It’s not just about showing off—though yes, a well-stocked bookshelf does signal intellect and curiosity—it’s about creating a space that feels like the physical manifestation of a mind at work. A personal library is simultaneously a refuge, a conversation starter, and perhaps most importantly, a reflection of who you are.

Here are some of my thoughts on crafting a home library that will both serve your intellectual life and subtly impress anyone who crosses your threshold.

The Physical Space: More Than Just Storage

First, let’s talk about the container before we discuss the contents. Great home libraries aren’t just functional; they’re atmospheric. Dark woods—walnut, mahogany, oak—tend to create that classic library feel, but don’t discount more contemporary designs if they better suit your space. What matters most is quality and sturdiness. Books are heavy, and cheaply made shelves will eventually sag in defeat.

Consider floor-to-ceiling shelving if your space allows. There’s something undeniably dramatic about a wall of books that draws the eye upward. If you’re working with limited square footage, floating shelves or built-ins around doorways can maximize space while creating architectural interest.

Don’t underestimate the importance of proper lighting. A good reading lamp (or three) is essential—warm light that falls properly on the page without creating glare. Articulating floor lamps that can be positioned precisely where needed make reading a physical pleasure. Consider the classic Anglepoise or a Tolomeo design if budget allows, or explore vintage options for character.

And comfortable seating is non-negotiable. Whether it’s a worn leather armchair with ottoman (the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman remains the platonic ideal for many), a window seat lined with cushions, or simply a cozy corner of your sofa, your library should invite lingering. Remember Bachelard’s observation in “The Poetics of Space” that corners are places “where one can retire into oneself.” Create such a corner with your seating arrangement.

Small touches complete the atmosphere—a side table for your tea or whiskey, a footstool, perhaps a map or globe, some personal objects that connect to your reading life. I’ve always admired libraries that include artifacts related to their books—a stone from a beach mentioned in a favorite novel, a postcard from an author’s hometown, a feather marking a passage about birds.

The Books Themselves: Hardcover vs. Paperback

Now, the eternal debate: hardbacks or paperbacks? The answer is both, but with intention.

Hardcovers are the workhorses of a serious collection. They last longer, stand up straighter on shelves, and generally look more impressive. For books you love deeply, books you’ll return to repeatedly, or particularly significant works, invest in hardcover editions. First editions, if you can find and afford them, add both intellectual and monetary value to your collection.

Consider specialty publishers who create particularly beautiful editions. The Folio Society produces illustrated classics with slipcovers that elevate any shelf. Everyman’s Library offers cloth-bound editions with acid-free paper that will outlast us all. The Limited Editions Club books from the mid-20th century, if you can find them, combine literary significance with artisanal bookmaking.

That said, there’s nothing wrong with paperbacks. They’re more affordable, lighter to hold while reading, and often feature more experimental cover designs. Many important works are only available in paperback. The key is condition—keeping them pristine, with unbroken spines if possible, though a well-loved book with a cracked spine tells its own story.

Vintage paperbacks from the 1950s and 60s—particularly those from New Directions, Grove Press, or City Lights—often feature striking modernist cover designs that look remarkable grouped together. Contemporary publishers like NYRB Classics have revived this tradition with their visually distinctive spines that create a pleasing visual rhythm when shelved together.

Some collectors swear by removing dust jackets while reading hardcovers to preserve them, storing them separately and replacing them when the book returns to the shelf. Others prefer the lived-in look of slightly worn books. Your choice here reflects your philosophy: is your library primarily for display or for use? The most interesting collections, in my view, show evidence of both.

Building a Well-Rounded Collection

What should actually fill these shelves? A truly impressive library contains multitudes. Here’s where to start:

Literary Fiction

The backbone of any serious collection. Include the recognized classics—yes, your Austens, Dickenses, Tolstoys—but don’t stop there. Add contemporary literary heavyweights and Nobel laureates. Make space for international fiction in translation; nothing says “well-read” quite like a shelf that spans continents.

Some specific recommendations that show breadth and discernment:

- The complete works of Italo Calvino, whose “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” is itself about the pleasure of reading

- Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov” for psychological depth

- Roberto Bolaño’s epic “2666,” a magnificent testament to literary ambition

- Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse” for modernist mastery

- Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” for magical realism

- W.G. Sebald’s “The Rings of Saturn” for its blend of fiction, history, and memoir

- Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick” for American epic

- Thomas Pynchon’s “Gravity’s Rainbow” to show you don’t shy away from challenging work

- Less expected choices like Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House”. also made into the riveting 1963 film “The Haunting,” or Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Left Hand of Darkness” that transcend genre

Include works that have shaped literary movements, from modernism to magical realism. And don’t neglect genre fiction of exceptional quality—the best of science fiction, mystery, or historical fiction often transcends category. A shelf containing Stanisław Lem’s “Solaris” beside Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon” and Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall” demonstrates range.

Arts and Culture

Books on visual art, music, architecture, film, or theater demonstrate cultural literacy. Large-format art books with quality reproductions double as beautiful objects in themselves.

Some worthy inclusions:

- John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” for visual literacy

- Alex Ross’s “The Rest Is Noise” for 20th-century music

- Robert Hughes’ “The Shock of the New” for modern art

- Camille Paglia’s “Sexual Personae” for cultural history

- Lewis Hyde’s “The Gift” on creativity

- Roger Scruton’s “Understanding Music” for philosophy of music

- Simon Schama’s “Landscape and Memory” for cultural history

- Kenneth Clark’s “Civilisation” for art history

Include works on the history and theory of art forms that interest you particularly. If you collect art books, organize them thoughtfully—perhaps chronologically, by movement, or by visual harmony when shelved together.

History

Historical works add gravitas to any collection. Include broad surveys of world history alongside more focused examinations of periods or movements that interest you. Primary sources and historical memoirs add depth.

Some standout selections:

- Edward Gibbon’s “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”

- Fernand Braudel’s “The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II” for its revolutionary approach to historical time

- Winston Churchill’s “The Second World War” series

- Barbara Tuchman’s “A Distant Mirror” for its accessibility and narrative power and “The Guns of August: The Outbreak of World War I”

- David McCullough’s “John Adams” for American biography

- Orlando Figes’ “A People’s Tragedy” on the Russian Revolution

- Simon Schama’s “Citizens” on the French Revolution

- Shelby Foote’s “The Civil War: A Narrative” for comprehensive American history

- The journals of Lewis and Clark or the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant for primary source material

Remember that today’s journalism is tomorrow’s history; quality reportage on contemporary events will age into valuable historical context. Collections like Tom Wolfe’s “The New Journalism” or George Orwell’s “Homage to Catalonia” capture their moments while transcending them.

Philosophy

Philosophy books signal serious intellectual engagement. Start with accessible overviews of major philosophical movements, then add primary texts from philosophers who intrigue you.

Some cornerstone works:

- Plato’s “Republic” and “Symposium”

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”

- Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics”

- Albert Camus’ “The Myth of Sisyphus”

- Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “Philosophical Investigations”

- Søren Kierkegaard’s “Fear and Trembling”

- Bertrand Russell’s “History of Western Philosophy” for accessible overview

- Roger Scruton’s “Beauty” for aesthetics

- Douglas Hofstadter’s “Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid”

Philosophy doesn’t need to dominate your shelves to make an impression—even a thoughtfully selected dozen titles shows depth. Consider also works that bridge philosophy and other disciplines, like Daniel Dennett on consciousness or Thomas Nagel on the mind.

Science

Science writing translates complex ideas for the layperson, and the best examples are as elegantly written as any novel. Include both classics like Darwin’s Origin of Species and contemporary works that explain emerging fields.

Some exemplary science books:

- Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time” the classic that everyone owns but few finish

- Oliver Sacks’ “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” for neuroscience with humanity

- Carlo Rovelli’s “Seven Brief Lessons on Physics” for elegant simplicity

- Richard Feynman’s “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!” for scientific joy

- James Gleick’s “Chaos” for making complex theory accessible

- Hope Jahren’s “Lab Girl” for memoir mixed with botany

- Edward O. Wilson’s “The Diversity of Life” for biology

- Stephen J. Gould’s “Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History” for evolutionary biology and natural history

Look for authors who make complex concepts accessible without oversimplification. A thoughtful science section shows you engage with our material world as deeply as with imagined ones.

Biography and Memoir

Lives well-documented add human dimension to a library. Choose subjects from diverse fields—artists, scientists, political figures, writers—to show the breadth of your interests.

Some remarkable life stories:

- Walter Isaacson’s “Leonardo da Vinci” for artistic genius

- Ron Chernow’s “Alexander Hamilton” for political biography

- Patti Smith’s “Just Kids” for artistic coming-of-age

- James Gleick’s “Genius” on Richard Feynman

- Hermione Lee’s “Virginia Woolf” for literary biography at its finest

- Edmund Morris’s “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt” for political life

- Vladimir Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory” for autobiographical brilliance

- Janet Malcolm’s “The Silent Woman” on Sylvia Plath

Quality matters here; look for biographies that go beyond mere chronology to offer genuine insight. The best examples become not just accounts of individual lives but windows into entire epochs or movements.

Political Science and Economics

Understanding how societies function is essential to being well-informed. Include classic political texts across the ideological spectrum, works on economic theory, and analyses of current systems.

Some important works:

- Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America”

- Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations”

- Edmund Burke’s “Reflections on the Revolution in France”

- John Locke’s “Two Treatises of Government”

- Friedrich Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom”

- Milton Friedman’s “Capitalism and Freedom”

- Thomas Sowell’s “Basic Economics”

- Jane Jacobs’ “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”

- Henry Kissinger’s “Diplomacy”

This section particularly benefits from including opposing viewpoints—it shows intellectual honesty rather than ideological entrenchment. A library with both Adam Smith and Karl Marx, both ancient and modern political theorists, suggests a mind willing to engage with all perspectives.

Essays and Criticism

Essay collections demonstrate intellectual curiosity. Include the established greats—Montaigne, Orwell, Emerson, Chesterton—alongside contemporary essayists.

Some essential volumes:

- George Orwell’s “Essays” for clarity and moral purpose

- G.K. Chesterton’s “Orthodoxy” for rhetorical brilliance

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s collected essays for American transcendentalism

- Michel de Montaigne’s complete essays as the foundation of the form

- John Jeremiah Sullivan’s “Pulphead” for contemporary mastery

- Joseph Epstein’s “Essays in Biography” for elegant profiles

- Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lectures on Literature” for brilliant close reading

- Roland Barthes’ “Mythologies” for semiotic exploration of everyday life

Literary criticism, too, shows engagement beyond passive reading; it signals that you don’t just consume books but think about them critically. Volumes like James Wood’s “How Fiction Works” or Harold Bloom’s “The Western Canon” demonstrate this engagement.

Poetry

Even if you don’t consider yourself a poetry person, a sophisticated library includes it. Start with comprehensive anthologies, then add individual collections from poets who speak to you.

Consider these varied but essential selections:

- Emily Dickinson’s complete poems

- T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets”

- Pablo Neruda’s “Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair”

- Elizabeth Bishop’s “Geography III”

- Seamus Heaney’s “North”

- Frank O’Hara’s “Lunch Poems” (especially the charming City Lights pocket edition)

- William Butler Yeats’s collected poems

- The collected works of Wallace Stevens for philosophical depth

- John Donne’s complete poems for metaphysical brilliance

Poetry collections make excellent browsers—books to pick up and sample briefly—and they often spark the most interesting conversations with guests. Beautiful editions like the Everyman’s Pocket Poets series look lovely grouped together.

Classic Children’s Literature

Don’t dismiss children’s books as solely for the young. The finest children’s literature contains wisdom for all ages. Beautiful editions of fairy tales, Alice in Wonderland, The Little Prince, or the works of Roald Dahl aren’t just nostalgic; they’re legitimate literary treasures that demonstrate breadth of appreciation.

Some titles that belong in any serious library:

- A.A. Milne’s complete Winnie-the-Pooh books

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s “The Little Prince” (preferably in both original French and translation)

- Lewis Carroll’s Alice books in an annotated edition

- The complete Brothers Grimm fairy tales, Jack Zipes’ translation

- C.S. Lewis’s “Chronicles of Narnia” series

- Norton Juster’s “The Phantom Tollbooth”

- Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar the Elephant books, French classic with wonderful illustrations

- E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web”

- The illustrated works of Maurice Sendak and Shaun Tan

These books often feature some of the most beautiful illustrations in publishing—Arthur Rackham’s fairy tales, Ernest Shepard’s Pooh drawings, or Barry Moser’s wood engravings for “Alice” create visual pleasure alongside literary merit.

Periodicals and Literary Magazines

Selectively preserved magazines and journals can add contemporary context to a library. Not everything needs keeping, but special issues of literary magazines, particularly noteworthy editions of cultural reviews, or journals containing first publications of important works deserve shelf space.

Consider collecting:

- The Paris Review for its influential interviews with writers

- Granta for its themed collections and photography

- First Things for intellectual religious discourse

- Commentary for cultural criticism

- Special issues of magazines like The New Yorker that focus on a particular theme

- Literary journals that published early work by writers you collect

These periodicals, especially when bound or kept in protective boxes, add a pleasing rhythm of smaller objects among your books and show engagement with ongoing cultural conversations.

The Art of Curation

Remember that a truly impressive library isn’t accumulated overnight or bought in bulk. It grows organically, reflecting your intellectual journey. Each book should earn its place. This doesn’t mean every volume must be profound—sometimes a book’s significance is personal rather than universal—but it should mean something to you.

Include some genuinely unusual items that reveal your distinct interests. Perhaps it’s an obscure work of speculative fiction like Stanislav Lem’s “Memoirs Found in a Bathtub,” a forgotten classic like Anthony Trollope’s “The Way We Live Now,” or a peculiar non-fiction work like Bruce Chatwin’s “The Songlines.” These unexpected choices often become the most interesting conversation starters.

Arrange your books in whatever system makes sense to your mind. Some prefer strict alphabetization by author; others group by subject, time period, or even color for visual effect. The organization itself reveals something about how your mind works. I know collectors who arrange books by the relationships between authors—mentors next to students, influences beside the influenced—creating a visual map of literary conversations across time.

Consider, too, the visual rhythm of your shelves. Mix formats and sizes. Allow some books to lie flat. Create small tableaux with objects related to nearby books. Leave some open space rather than packing shelves to their absolute capacity. As in good writing, the white space matters.

Finally, leave room—physically on your shelves and metaphorically in your collecting philosophy—for serendipitous discoveries. The most interesting libraries contain unexpected treasures, books found by chance that opened new intellectual territories. These surprises often become the most cherished volumes and the best conversation starters.

A truly enviable library, after all, isn’t just a status symbol. It’s evidence of a curious mind at work in the world, gathering ideas like precious stones, each one selected for its particular gleam. Build yours with intention, and it will reward you with both knowledge and quiet distinction. As Jorge Luis Borges, that great librarian, once suggested, “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.” Perhaps that’s because a great library is already a kind of paradise—one you can build yourself, book by book.